If you read last week’s blog post you already know that I’ve got three months to put together a physical demo for a PyCon talk about factory automation. This post is the first in a series of progress updates.

In robotics and automation, the smallest realistic demo has three parts: Sensing, control, and actuation. I spent Week 1 selecting and bargain hunting for an industrial barcode reader to cover the sensing part of the demo. As I went along I wrote up my notes as an “Introduction to Barcode Readers”; if you only want to know what I ended up buying, scroll down to the end!

Why not just install a barcode reader app on your phone?

Of all the types of sensing devices, barcode readers are probably the most ubiquitous across all industries that deal with discrete items1. Some of the coolest demos at automation trade shows are those where barcode readers find and decode barcodes on disks spinning so fast that the human eye only sees a blur: Video 1, video 2, video 3.

Barcode readers come in both a handheld form factor (natural habitat: hardware store checkout, fulfillment center) and the fixed mount form factor (natural habitat: above conveyor belts). What you see at the grocery store checkout is a single reader combined with an assembly of static and rotating mirrors that result in the scanner “looking at” the item from many different angles in rapid succession.

I told someone at the San Francisco Python meetup that I’m working on a driver for this barcode reader that I was carrying around in my back bag that day. After a second of confusion, he points at the device and says: “I’ve got a barcode scanner app on my phone, why would I buy one of these?” Let’s get the “software vs hardware” question out of this way first.

There are several powerful open source libraries available for reading2 barcodes, most of which are available within the Python ecosystem3. The most popular (I think) implementation in C is zbar for which Python bindings are available on PyPi. If you need a Java implementation, for example, because you are writing yet another Android barcode scanning app, zxing (pronounced “zebra crossing”) is a common choice.

zbar and zxing can read all barcode formats found in retail, but coverage of other formats is spotty. I once tried to read Datamatrix barcodes in Python and quickly found out that I’m out of luck with zbar. With more obscure formats there often are specialized libraries for just one barcode format, and for Datamatrix, I found the unmaintained libdmtx, but struggled to get the (included) Python bindings to work. My final (and successful!) attempt was to switch to IronPython which allows for calling .NET libraries such as this .NET port of libdmtx.

Format coverage aside, the bigger problem with all of these solutions is that any Frankenscanner you might build by combining these libraries with a phone camera or webcam will be nowhere near as fast or accurate or error tolerant as even a cheap off-the-shelve device4. Of course, sometimes a laggy phone app is exactly what you need, but in factory automation, it usually isn’t.

Purpose-built devices are better because they can be designed to optimize every step of the conversion from light to data specifically for the application of reading barcodes: The lenses can be optimized for best field of view (but don’t care much about distortion), image sensors can be optimized for contrast (but don’t care much about color accuracy), and processors are optimized for graphics (but don’t care much about web browsing performance).

The bottom line is: If you want to read barcodes in the real world, do yourself a favor and buy a barcode reader.

Barcode Formats

A barcode isn’t a barcode isn’t a barcode. And not every scanner can scan every type of barcode. In normal situations, your application dictates what type of barcode you need to scan. Since I can do whatever I want for my demo, I don’t have to deal with that and can just generate my barcodes to match the capabilities of my (yet to be selected) barcode reader. It’s still a good idea to know what types of barcode scanners exist because not every reader technology can read every type. So let’s do a quick tour of the world of barcodes5.

When I write “barcode format”, I mean two things: The physical shape of the barcode, and the methodology by which it can be converted to human-readable text. Usually, these two are coupled, the same standard document that describes the shape of the barcodes also specifies the symbology6.

As for physical shape: There are 1-dimensional (linear) codes and 2-dimensional codes. Half way in between there are stacked codes which are basically multiple 1-dimensional codes side by side.

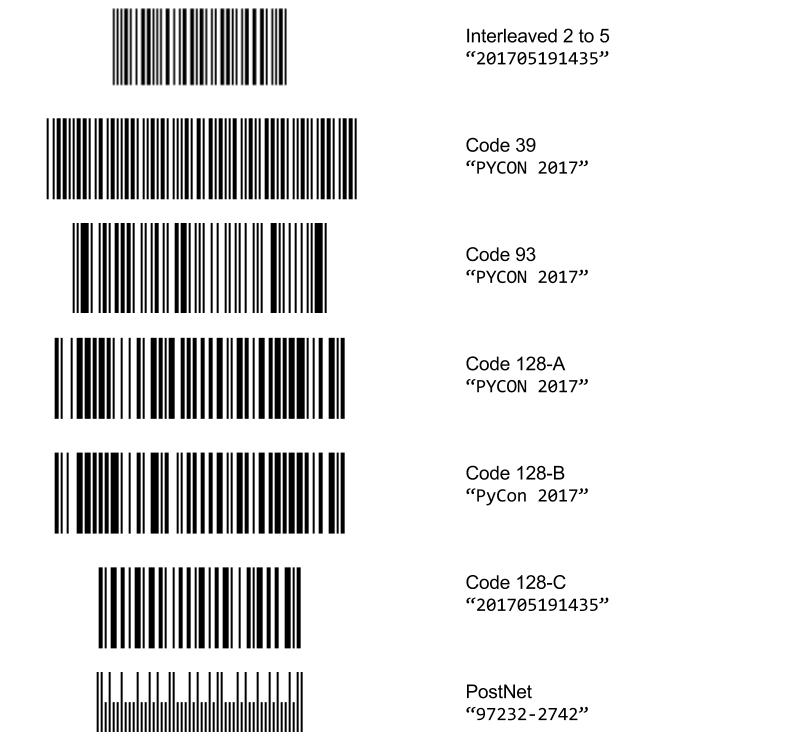

The figure above shows a few example of 1-dimensional barcodes7. Wikipedia has a wealth of information on each format

- Interleaved 2-of-5 (ITF) – Numeric only, five fixed-width bars encode a pair of two digits, hence “interleaved”.

- Codabar – Seven fixed-width bars encode 16 characters (

0-9,$,+,-,:,.,/), apparently still popular in libraries. - Code 39 – Nine fixed-width bars encode 43 characters (

0-9,A-Z,$,%,.,,-,+,/). - Full ASCII Code 39 – Same as Code 39, but uses 18 bars to encode 255 chars.

- Code 93 – Six variable-width bars encode the same characters as Code 39 in less space

- Code 128 – Six variable-width bars encode 128 characters. There are three subtypes with different character tables (see below).

- GS1-128 (EAN-128, UCC) – Subset of Code 128 with application specific fields such as expiration date, shipping container number, etc.

- UPC-A – Four variable-width bars encode numbers only. This (or it’s EAN-13 equivalent) is the barcode format found on every product in retail stores.

- UPC-E – Serves the same purpose as UPC-A but is only six characters long. It’s meant for packages that are too small for the UPC-A barcode, for example chewing gum packages.

- EAN-13 – International version of UPC-12. EAN-13 is a superset of UPC-12, prefixing any UPC-12 barcode with a number

0turns it into the equivalent EAN-13 code. For all EAN-13 codes that don’t start with a0, there is a list of prefixes. - EAN -2 and EAN-5 are additional barcodes placed next to an EAN-13 barcode to hold supplementary product information, for example, the issue number on magazines or the suggested retail price on a book

- EAN-8 – Same story as UPC-A vs UPC-E.

- Pharmacode – Variable number of black/white bars encoding numbers between

3and131070in binary - PostNet – 5-7 fixed-width varying height bars to encode a digit. Used by USPS for zip codes.

- KarTrak Large multi-color codes that were on 90% of US railroad cars in the 1970s.

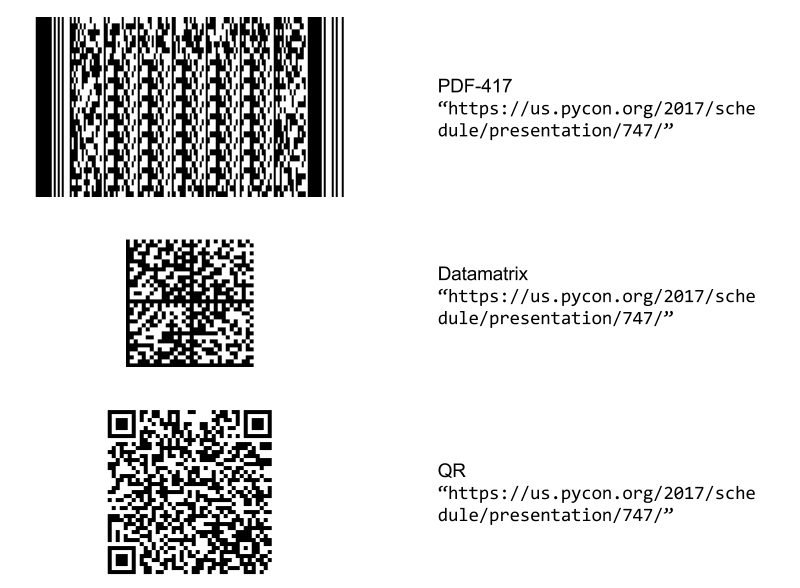

There are fewer commonly used stacked and 2-dimensional barcode formats than there are 1-dimensional ones, probably because the technology to read them has been around for a shorter time span. For the sake of completeness, here’s the list including links to Wikipedia:

Stacked:

- PDF417 Wikipedia – These are often used on flight boarding passes, the encoding contains almost 1000 “words” and is complicated.

- GS1 Databar (RSS-14) – A family of formats that include UPC-A and EAN-13 where the bars are arranged in multiple (usually two) rows instead of a single one, basically a barcode with “line breaks”.

- Several other formats that consist of multiple 1-dimensional codes placed on top of each other, or a single 1-dimensional code spread over multiple rows.

2D:

Of the symbologies I am familiar with of, Code 128 has the most complex encoding. There exist three different variants, Code 128-A through C. All three variants use non-interleaved “building blocks” that represent seven bits each. Wikipedia has the table of mappings from bit value to text representation:

- Code 128-A contains numbers, uppercase characters, and control characters.

- Code 128-B contains all 127 ASCII characters.

- Code 128-C has dedicated patterns for numbers from 0 through 126

The benefit, of course, is that you can use any ASCII character with Code 128-B but can also get very dense numbers-only barcodes with Code 128-C. But wait, there is more! There are control characters to switch between variant mid-string! To print a string like AbcD123456 in Code 128, you would start with four characters of Code 128-B (because A is the one with lowercase characters), then a control character followed by three characters (representing 12, 34, and 56) in Code 128-C (because C is the one that needs least linear space for numeric strings). Or you could just use Code 128-B for the entire string. Yes, this means that the same text string has multiple Code 128 representations. It also means that the length of the barcode is not proportional to the length of the string it encodes. In fact, a shorter barcode could represent a longer string.

One more thought about barcode formats: If you think about it, 2D barcodes shouldn’t be called barcodes because there aren’t any bars in them. “Boxcodes” maybe. Anyway, moving on.

How it works: Scanner vs Imager

Up until 20ish years ago, laser scanners were the only game in town8: A single laser shines on a moving mirror such that the laser beam is swept through the “field of view” of the scanner. A single photodiode continuously measures how much of the laser light gets reflected. This measurement will rapidly change between “barely anything reflected at all” and “lots of reflection” as the laser sweeps over a pattern of dark lines on light ground. Threshold the time history of the measurement, do a little bit of pattern matching, et voila, you’ve got a laser scanning barcode reader. Laser scanning really only works for 1-dimensional codes. Some modern devices use software trickery to provide limited support for simple stacked formats.

When CCD technology became viable (in the mid-1990s?), people put a single line of CCD pixels next to each other and called it a linear CCD imager. A few LEDs surround this line-of-pixels sensor and shine light at any barcode that happens to pass by. The CCD takes a “picture” (1 pixel by n pixels) to get a string of brightness values. The data processing to turn these brightness measurements into barcode data is effectively the same as what you’d use with the time history measured by the laser in a laser scanner. The same restrictions apply as for laser scanners.

Finally, 2D imagers. These are basically digital cameras that take images that are analyzed by computer vision algorithms to find the geometrical features that make up the barcode. The specs by which you purchase imagers are similar to what you’d select a DSLR by: Resolution is important, the higher the resolution the further away the barcode can be (or the smaller, if that’s what you’re after). For some people, shutter speed is important because it defines how fast you can move the barcode past the camera without getting a blurry image. Other DSLR specs don’t really matter, such as color accuracy. Often you get these for free, though, because the same hardware you purchase as a barcode imager might also be sold as optical inspection instrumentation (the embedded software and the price tag will be different).

How do you recognize what type a barcode reader is? Here are a few tricks:

- If you point your barcode scanner at a surface and you see a pattern of distinct lines, you are holding a laser scanner. Linear CCDs and imagers have a diffuse light. I’m not sure why, but it seems like linear CCDs use red light while imagers use green.

- If you hear a humming sound or feel a vibration when you touch the device, it’s also got a laser scanner. Remember, there is a rotating mirror inside every laser scanner that is constantly in motion. By the way: The moving parts are a big drawback of laser scanners. Like with everything else (hard drives!), solid state devices run circles around devices with moving parts when it comes to reliability.

- Another thing you can try is scanning a barcode from a phone screen: It won’t work with laser scanners because the laser light gets reflected at the outer glass surface of the screen before it can reach the pattern. That’s why you have to type in your phone number at the grocery store checkout to get your “loyalty points” – if they had imaging barcode readers they’d probably let you swipe your phone like at the airport gate.

I’m sure that there’s a lot more to be written about reader technology, but until now I have gotten away without doing a deep dive into this material. Besides, when I got to this point in the blog post I really just wanted to make a decision on what reader to buy.

Interface

The point of scanning the barcode is rarely to just show the text content of the code in a human readable format on a screen and move on. More often than not, the barcode is destined for a database (e.g. inventory tracking) or part of a decision-making process (e.g. how much the store customer needs to pay for the items in their shopping basket).

The way this is almost always done is a great example of keeping it simple stupid. Barcode readers are plugged into the computer like a keyboard and act exactly like a keyboard.

At a checkout register the process is this:

- The cursor is always active on the form field for the next EAN-13 code.

- When the barcode reader reads a barcode it “types” it into the form field

- Because the barcode reader is configured to append a carriage return to every barcode, the form gets submitted and the process starts from the beginning

The best part is: If the scanner fails to read a barcode, the cashier can type in the EAN-13 using the regular keyboard and hit enter – no separate workflow needed for the error recovery!

Every barcode scanner (that I know of) can be set up in this fashion as a “keyboard” with minimal effort. The mechanics differ by device:

- Many handheld devices have a PS/2 port or USB cable built in

- More new-fangled devices connect to the host computer via Bluetooth and register themselves as Human Interface Device

- Other require a “keyboard wedge” accessory that converts from the built-in cable to PS/2 or USB

The caveat with this “as-a-keyboard” setup is that it always requires a host computer. If you have a factory with hundreds of barcode scanners, that would quickly get pricey and annoying. That’s (probably) why non-handheld barcode readers often come with a serial port (RS-232), which makes them a bit more versatile. You could use these with:

- A computer that has a serial port

- A computer and a USB-to-serial converter

- The keyboard wedge accessory that’s probably available in the manufacturer catalog

- To a programmable logic controller (PLC) with an RS-232 port

- To an RS232 server (a gadget that makes serial devices available over Ethernet)

With Python, you could imagine going either route: as-a-keyboard or serial device.

If your reader has an RS-232 interface, you can use the actively maintained and very mature pyserial package to connect to the serial port. If your barcode reader acts as a keyboard, you could just call input() to read a barcode and wait for the reader to send content. The big caveat with that latter method is that you can really only have one barcode reader per machine9.

Bargain Hunting on Ebay

I started shopping around for barcode readers with this list of requirements:

- Under $50

- RS-232 interface

- Must have detailed manual/documentation available

- Prefer small unit with mounting holes over handheld “gun shaped” ones

- Should support a range of symbologies

That last point is worth noting. Most barcode reader shoppers probably have one specific barcode type to support, which limits the selection right out of the gate. Because I can make up my “application” as I go along, I decided to get the barcode reader first and then decide on what barcode type to use.

Shopping for commercial and industrial equipment can be a bit of a pain because most manufacturers and distributors don’t have prices listed on their websites. Instead, they want you to request a quote and once you do, they will never stop emailing and calling you. Being in a rush and price conscious makes it a no-brainer to shop for used equipment, and Ebay is (still) the place where those things get listed10.

The most relevant categories are Other Automation Equipment and Point of Sale (POS) Barcode Scanners. But, of course, not every seller does a great job to classify their items, and incorrectly classified items are often the best bargains because they are easy to miss when searching.

I was pretty excited about a Keyence SR-501. Checks all the boxes and supports all common 1D and 2D barcode types. The 17-28 days delivery time from Thailand was a show stopper :/

I ended up buying an MS3 from Microscan for $29.99, a compact little laser scanner. Obviously, this limits my demo to 1-dimensional barcodes but this one has a few things going for it:

- Not handheld, I wanted a compact easy to mount unit

- Very detailed (200 pages!) and freely available documentation

- Doesn’t require special software to configure, just serial commands covered in documentation

- Just in case, there’s also a freely available Windows software

The day after buying the MS3 I was browsing around the Microscan website and saw a discontinued 2D reader model called MS4. It’s a “legacy product”, but my understanding is that this is actually an imager that can read most 2D symbologies while having the same well documented serial command interface as the MS3. Feeling lucky, I typed “Microscan MS4” into Ebay and sure enough found one in the “Automotive” section for $25. Talk about misclassified bargains. I ended up buying that as a backup.

Next Steps

Ok, now I wrote everything I know about barcode readers up in a 3500-word blog post and purchased two barcode readers off Ebay. What’s next?

The next two big items on my todo list are:

- Write a Python driver for these barcode readers. You can follow along on Github: https://github.com/jonemo/microscan-driver

- Purchase a conveyor belt. This one worries me because these things can be heavy and bulky and expensive. And I need one that I can afford and bring to Portland in a suitcase. I’ll write a blog post about it when I figured it out…

One more thing: The talk abstract for my talk is now up on the PyCon website.

Footnotes

If you are dealing with bulk items like oil, coal, or lego bricks, barcodes are less useful for obvious reasons. ↩︎

Reading a barcode involves two steps: Step 1 is detecting (finding) the barcode in an image. Step 2 is decoding a barcode at a known location. The output of barcode detection is a set of pixel coordinates and rotations. The output of barcode decoding is the content of the barcode, which depends on the barcode type used but is usually human readable text. ↩︎

Wondering why I’m emphasizing Python? Remember, this is a progress update on preparing a PyCon talk ;) ↩︎

A good use case for software libraries for barcode reading are when you only have the digital image of the barcode to start with, for example when people are faxing barcoded forms to your fax-to-email gateway or when you are pursuing mischievous activities with Instagram photos of boarding passes. ↩︎

If you were looking for the long version of the tour, try this wonderful site: http://www.adams1.com/ (note that the footer says “Copyright 1995”) ↩︎

Symbology describes the mapping between geometrical features in a barcode (lines, squares, dots) and characters (or other content). ↩︎

Most of the barcodes in these figures are made with online tools from http://generator.onbarcode.com/ ↩︎

That explains why “barcode scanner” is often used as a generic term for all barcode readers, including imagers. ↩︎

Maybe there is a way to pipe different keyboards to different shells or services? ↩︎

In industry-heavy areas like Silicon Valley it’s also worth checking Craigslist. I usually do, but until now I’ve always found a better deal on Ebay. ↩︎